|

Farming the Fungi Kingdom - Organically

By Jason Witmer

Mushrooms should be a critical part of agriculture, they’re

the recyclers,” says Thomas. “We’re growing all kinds of

fibers and we’re throwing them out and dumping them in

landfills. I can grow oyster mushrooms on shredded soy-ink

newspaper.”

The

Wiandts produce a variety of mushrooms in just a few small

buildings nestled among an old-growth forest. They have made

this pursuit economically viable enough to leave their former

careers, and they contend that in an ideal society,

mushrooms—grown on entirely waste products—could provide an

extremely efficient protein source. The

Wiandts produce a variety of mushrooms in just a few small

buildings nestled among an old-growth forest. They have made

this pursuit economically viable enough to leave their former

careers, and they contend that in an ideal society,

mushrooms—grown on entirely waste products—could provide an

extremely efficient protein source.

Four years ago, the two were sitting unhappily behind

desks—Thomas was an engineer, and Wendy was a medical

technologist. Looking for another kind of life, the two saw

potential in their mushroom-collecting hobby. “We were both

professionals with desk jobs and wanted to get the heck away

from that,” Thomas says. “I grew up on a farm and I always

wanted to get back to a small farm type of living.”

“We did a lot of research and looked at several different

possibilities,” he recalls. “Mushrooms are a good fit.

Everything always breaks and I’m always fixing everything—so

that suited me. And this is probably the most laboratory

intensive kind of farming there is.” That suited Wendy, who

had spent time working in a medical laboratory.

Though they still hunt and market wild mushrooms from their

46-acre, organically-certified woods, they now specialize in

homegrown oyster, shiitake, and lion’s mane mushrooms. These

go to farmers' markets, retail outlets, and restaurants

A different kind of farming

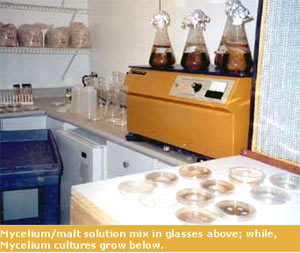

The process of growing mushrooms begins with mycelia, which

the Wiandts isolate from the wild or, more often, purchase in

a t est

tube from a laboratory. As beer brewers do with yeast, the

Wiandts drop bits of mycelia into a malt sugar solution. They

leave them there for a couple weeks until the concoction looks

like tapioca pudding. est

tube from a laboratory. As beer brewers do with yeast, the

Wiandts drop bits of mycelia into a malt sugar solution. They

leave them there for a couple weeks until the concoction looks

like tapioca pudding.

Once the mycelia are mature, they put small samples of the

liquid broth into bags of sterilized rye grain, seal the bags

and transfer them to a room held at 75 degrees. After about

two weeks, when the mycelia have spawned, the Wiandts

distributed the rye through bags of packed straw or sawdust.

After another two weeks, the mushrooms begin fruiting out of

holes poked in the bags. The mushrooms fruit up to five times

and Thomas and Wendy harvest them twice a day.

The most difficult thing about the process is keeping out

contaminants, such as molds. If contaminants enter the bags,

the mushrooms will not fruit and weeks of labor are wasted.

Each transfer must be done in a sterile environment—by using

laminar flow hoods and sterilizers, and an electronic

filtration system for removing spores from the air. “A lot of

the work is more difficult than the work Wendy used to do in

the hospital laboratory,” Thomas says.

The Wiandts are experimenting with growing hen-of-the-woods

and shiitake mushrooms outdoors on rotting logs, which seems

to be as efficient as growing them indoors. The process is the

same except that they inoculate dowel plugs with mycelium,

instead of rye. They insert these into the logs and seal them

with beeswax.

|

Mushrooms are so absorbent – they’re sponges. How can

you put pesticides on those? That’s just not acceptable. |

Pest control is the biggest factor

separating Killbuck Valley mushrooms from those that are

conventionally produced. Conventional mushroom producers use

large amounts of pesticides because mushrooms attract many

pests, including birds and insects. But the Wiandts are

strongly against using chemicals. “Mushrooms are so

absorbent—they’re sponges,” says Thomas. “How can you put

pesticides on something like that? It's just not acceptable.”

Without chemicals, the Wiandts must control pests manually,

and this is much more labor intensive. They use a rotation

schedule in rooms, separating new bags from older ones, so

that pests don’t spread. They also use screening and

filtration to keep insects out of rooms and sticky strips to

catch those that do get in. If a column gets too contaminated

they throw it out prematurely instead of treating it with

chemicals.

Sizing up the mushroom market

Unfortunately, because mushrooms are such an unusual product

already, the Wiandts don’t receive a higher price for being

organic. There are two outlets that buy from them because they

don’t use chemicals, but they don’t pay any more. “There’s a

lot of added expense in being organic,” Thomas says. “It’s

just something that we happen to believe in.”

Nonetheless,

the Wiandts are doing well economically. This is in part

because they are the only small-time grower in the region.

Since mushrooms don’t transport well, Killbuck Valley's

products look much better than those from large commercial

producers. Nonetheless,

the Wiandts are doing well economically. This is in part

because they are the only small-time grower in the region.

Since mushrooms don’t transport well, Killbuck Valley's

products look much better than those from large commercial

producers.

The Wiandts get their highest price at farmers' markets, which

make up more than half of their sales in the summer. They

receive $7.50 a pound for oyster mushrooms and $9.50 a pound

for shiitake. To reduce waste, Wendy has begun pickling the

mushrooms they don’t sell. They now have a licensed cannery

and sell the pickled mushrooms at market.

The Wiandts feel that contributing to farmers' markets is

important. “Organic or not, there are no commercial producers

at the farmers markets,” Thomas says. “They’re all small

farmers, good people, very ethical people. If you go there

you’re making your society a better place—automatically.”

The markets also give the Wiandts a chance to promote and

educate people about their product. “We can sell tons more

products at the farmers' market, at a higher price, because

we’re there educating people and talking to people and

developing relationships,” Thomas explains. “And putting out

samples so folks can try them." Offering samples is critical,

the Wiandts say, because people are are naturally reluctant to

pay for a premium product they may have never tasted before.

The Wiandts seek to dispel the myth that mushrooms don’t

contribute to a healthy diet. Mushrooms are actually high in

carbohydrates, contain up to 30 percent protein—including

important amino acids—and are high in mineral content. There

are also studies being conducted on the immuno-stimulus

properties of mushrooms such as oyster and shiitake.

“Everybody thinks mushrooms have no nutritional value because

the USDA doesn’t have them on their charts,” Thomas says.

“They need their own category,” Wendy suggests. “The fungus

category.”

After having promoted their products at farmers' markets for

years, the Wiandts have now had more success with retail

stores and restaurants because customers are beginning to

recognize their products. While they only receive about 70

percent of the market price from restaurants and retailers,

the loss in profit is about the same as the extra expense they

put into selling retail. Selling to these venues also

increases their efficiency at market because they can sell

more when they go only once every two weeks.

"Organic or not, there are no commercial producers at the

farmers markets. They’re all small farmers, good people, very

ethical people. If you go to those you’re making your society

a better place – automatically."

The Wiandts feel that producing year-round is a key to their

successful restaurant trade, accounting for over 50 percent of

their sales during the winter. Though they make no profit

during these months, due to increased labor and decreased

sales, they maintain customers.

“If we were just producing in the summer the customers would

go elsewhere and we wouldn’t have the good relations with

restaurants,” says Wendy. “That’s a huge issue with the chefs.

They want somebody they can rely on. If they have an item on

the menu, they want to make sure that they can leave it on the

menu.”

“Chefs aren’t looking for a bargain,” Thomas agrees. “Chefs

are looking for good reliable products, and good, long-term

relationships. They’re willing to pay a little extra if they

know it's going to be good stuff all the time and they don’t

need to worry about it.”

Tending a business, and attending to community

The Wiandts pay close attention to the economic side of their

business so that they won’t

have

to return to their old desk jobs. They also stay active in the

agricultural community. They have recently hosted wild

mushroom hikes for chefs and public events for the Ohio

Agricultural Research and Development Center. have

to return to their old desk jobs. They also stay active in the

agricultural community. They have recently hosted wild

mushroom hikes for chefs and public events for the Ohio

Agricultural Research and Development Center.

Thomas is also a member of the Ohio Farm Bureau – a lonely

place for someone with his values. “It's extremely unusual for

an organic farmer, because the Farm Bureau has an anti-organic

agenda,” he says. “But I figure you can’t have any say if

you’re not there. The more organic farmers abandon it, the

worse it’s going to get. So I try to stay active and put my

two bits in.”

"Chefs aren’t looking for a bargain. Chefs are looking for

good reliable products, good relationships, and long term

relationships. And they’re willing to pay a little extra... to

make sure that it’s going to be good stuff all the time."

The Wiandts believe that mushrooms have an important role to

play in the future of our society, noting that several Asian

countries make widespread use of mushrooms because they don’t

have the space to produce more conventional commodities like

beef.

“What we’re working on is a fundamental shift in the way we

use food and the way we think about agriculture,” says Thomas.

“We try to change the world in our own little way.”

Rare fungi flavors beggar description:

Here's a short flavor guide to some of the varieties Killbuck

Valley grows:

Shiitake –

The name means “oak mushroom” or “fragrant mushroom.” It

grows well on non-aromatic hardwoods. It has a powerful,

distinctive flavor. The Wiandts like it in a hot and sour

soup.

Lion’s mane –

Also known as “mock lobster.” It has a very sweet, rich,

distinctive flavor and sautés wonderfully, even by itself. It

doesn’t mix as well because it gets lost and is best as an

accent item.

Oyster mushrooms –

Thomas calls them “the chicken of the mushroom world”

because they go well with many things. They are mild, have a

pleasant flavor, a wonderful texture, and their appearance is

beautiful in a dish. They are often cooked with seafood,

chicken, or pasta.

Blue oyster –

A heavy, meaty mushroom with a moderately firm texture and

rich flavor. It is often used with red meat

White oyster –

The classic oyster mushroom and similar to the oyster

mushrooms native to Ohio. It is sweet, mild, smaller than the

blue oyster and has a touch of anise.

Italian brown oyster –

A very rich mushroom, more tender than the other oysters,

and with a bit of an eggy flavor. It is often used in pasta.

Golden oyster –

Often described as citrusy, nutty, and crunchy. It is

popular in stirfries and salads.

Pink oyster –

The firmest of the oysters. The flavor is excellent—very

strong and rich, with a touch of watermelon.

Curtsey: The New Farm

|

Pakissan.com;

|